To ensure learning continuity during COVID-19 and enable teachers to effectively adjust to the emerging circumstances, education systems in the Global Partnership for Education (GPE)’s partner countries in Africa provided teachers with training and support. The presence of the teachers within communities made them easily accessible and suitable as frontline responders. Thus, teachers were among the earliest to reach communities through outreach initiatives that targeted the overall well-being of parents and learners.

However, efforts to ensure that learning continued could not fully succeed without addressing the role and capacity of teachers and overcoming pre-existing teaching barriers. Generally, most teachers in sub-Saharan African (SSA) contend with large class sizes, limited teaching and learning materials and financial resources for schools, and inadequate resources for teacher professional development (TPD) initiatives. Additional evidence shows that a limited emphasis on digital-aided learning in professional development largely contributed to the distance learning solutions (DLS)’ teaching skills gap witnessed during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Hence, this policy brief presents available evidence on the policy and practice responses in teacher training and support during the periods of school closures and re-openings in 40 GPE partner countries in Africa. It is one of several outputs of the Knowledge and Innovation Exchange (KIX) Observatory on COVID-19 and is based on a synthesis report examining countries’ policy and practice responses to teacher training and support.

GPE partner countries have faced numerous challenges in trying to improve teaching effectiveness during the COVID-19 pandemic period.

The following are some of the documented challenges:

1. Loss of employment, with female teachers disproportionately affected due to their dual role as professionals and primary caregivers in their households.

2. Private school teachers were less likely to have their salaries continued during school closures and had less access to professional development.

3. Lack of robust infrastructure to support distance learning, especially in rural and remote areas, and many teachers struggling to adapt DLS tools and approaches to meet the needs of students with special needs

4. Inadequate financial resources to support teacher training in most countries. Thus, many teachers were ill-prepared to support students during school closures and re[1]openings.

5. Internet connectivity challenges, which impeded continuous access to online training for teachers.

6. Insecurity and safety challenges for teachers from conflict zones, and the difficulty of adapting training modules to insecure conditions, including through offline resources

To overcome the above-mentioned challenges, training and support focused on six inextricably linked themes. The first four below are relating to teacher training and the last two on teacher support.

Training in the Development and use of Distance Learning Solutions

The teacher training encompassed the development and use of distance learning solutions and pedagogical strategies to ensure continuity of learning and deliver catch-up lessons to mitigate learning loss. DLS tools and platforms included Internet-based platforms and applications as well as radio and television. DLS training also included the creation of teaching materials for learners with special education needs, such as large print resources for the visually impaired.

and approaches by country, 2020

Source: KIX Observatory: Teacher Training and Support in Africa during the COVID-19 Pandemic

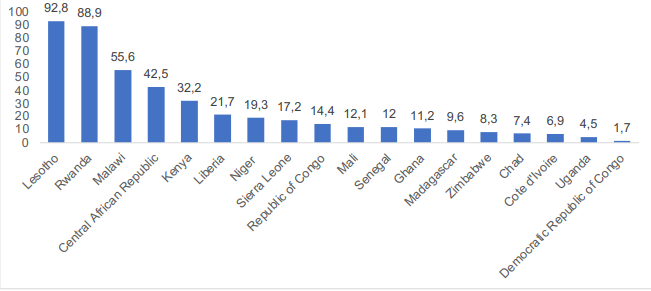

All 40 GPE partner countries in Africa provided at least one type of training in using DSL tools and approaches, though not all teachers were reached. 21 countries out of the 40, provided training on the development of lesson plans, teaching plans and guides and instructional models through DLS. 11 countries trained teachers to use these tools to remotely monitor learning and administer adapted learning when schools reopened.

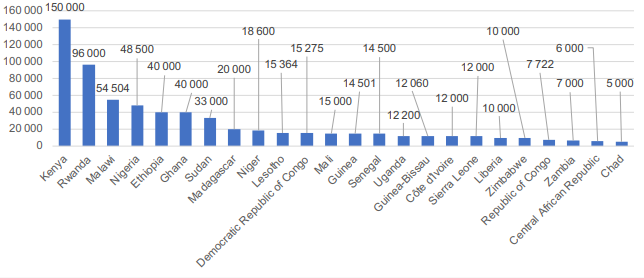

In Sierra Leone, approximately 12,000 teachers were trained in the use of various DLS platforms for teaching and administration to ensure continued learning during the school closure period. In Ethiopia, GPE trained 4000 master trainers and 40,000 teachers at a cost of US$400,000 and US$1,000,000 respectively.

approaches by country, 2020 Source: KIX Observatory: Teacher Training and Support in Africa during the COVID-19 Pandemic

Based on a country’s capacity to finance professional development activities, the proportion of teachers trained varied. For instance, more than half of all teachers were trained in Lesotho, Rwanda, and Malawi, while less than 2% were trained in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC). In at least five GPE countries, private sector partners worked with government to provide teachers with free or subsidized access to the Internet. Côte d’Ivoire, Kenya, and Rwanda embarked on intensive capacity building to enable teachers to deliver lessons using innovative approaches, not bound by physical space. This allowed teachers to not only use distance education media, but to be creative in using them to develop and share lessons and teaching materials.

Mitigating Gender-based Violence and Promoting Mental Health

The prolonged school closures due to COVID-19 exposed school children, especially girls, to both physical and psychological violence. Teachers therefore needed training on mitigation strategies and ways to support children exposed to the abuse. 10 of the 40 GPE countries offered teacher training on how to identify and mitigate Gender-based violence (GBV) and refer victims to support services. Teachers also received training on support to vulnerable children – including those with disabilities, displaced school children, and those from poor and/or remote backgrounds.

Lesotho provided 15,364 teachers with information on GBV risk mitigation, including a stepwise approach to preventing sexual exploitation and abuse, safe referral practices, and child safeguarding during school closures. The training was conducted via four series of mobile phone messaging to targeted teachers. At a cost of US$0.08 per message for every teacher (GPE, 2020z), a total of US$4,916 was used for this purpose.

Teachers in Uganda and Zambia were trained on how to identify learners who were experiencing various challenges due to COVID-19. They were then expected to offer such learners appropriate psychosocial support through phone and text during their routine student monitoring activities:

School Reopening Preparations

Training to support preparations for school reopening focused on two main areas: pedagogical preparedness measures, such as adapting teaching strategies to help students catch up, and health and sanitation measures to prevent school-based infection. To facilitate school reopening, 11 countries offered some form of training in pedagogical approaches to help students close the “lost learning” gap, which include pedagogical strategies such as Teaching at the Right Level and catch-up teaching. Other aspects of training included how to identify and categorize learners into sub-groups depending on their learning needs, teaching literacy and numeracy skills, and using formative assessment to support learning. A few notable in-country examples include Sierra Leone where the Ministry of Basic and Senior Secondary Education (MBSSE) trained approximately 984 trainers of trainers (ToTs) in preparation for school reopening. These ToTs in turn would train over 23,000 primary and secondary school teachers countrywide on how to implement these protocols – mainly focused on health and hygiene related practices – when schools reopen. In Cameroon, the preparations undertaken prior to schools’ reopening included teacher training on remedial learning using distance learning approaches to make up for learning hours lost during the school closures. Teachers were also prepared to maintain appropriate psycho-pedagogical support to learners when classes resume.

Prior to reopening, teachers from 23 GPE partner countries were also supported and trained on recommended WASH (water, sanitation, and hygiene) guidelines, largely through radio, television, and Internet, to prevent school-based infections. Sanitation and hygiene training in these countries was accompanied by other WASH measures, including intensive disinfection of schools and the provision of personal protective equipment (PPE).

Supporting Vulnerable Children

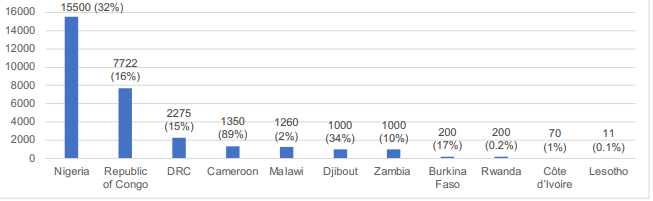

Vulnerable children include those with special needs, displaced school children, those living in rural, remote settings, and those from low-income backgrounds. The pandemic exacerbated exclusion in learning for these children, with estimates indicating that nearly 40% of least developed and lower-middle[1]income nations are unable to support learning for vulnerable children. In SSA, teachers feel that they are not adequately supported with essential learning resources to attend to school children with special needs. For example, 41% reported that the lack of personal assistants was a barrier in their efforts to support learners with disabilities. Notwithstanding these limitations, 14 GPE partner countries (see Figure 3) provided teacher training to address the learning needs of vulnerable school children. This covered various approaches such as the use of interpretative signing, closed captioning, large print documents, and other sound or visual adaptations, among others.

schoolchildren Sources: ActionAid (2021); Government of Côte d’Ivoire (2020); Government of Malawi (2020b);

Government of Zambia (2020); GPE (2020k, 2020p, 2020zb & 2020zc); World Bank (2020c)

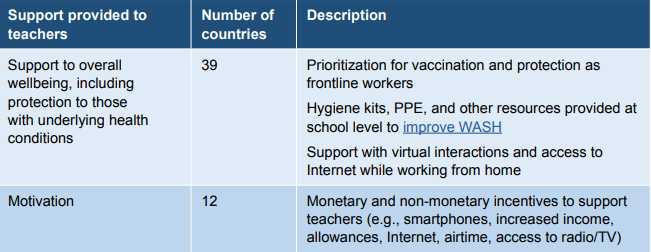

Teachers Overall Wellbeing

In addition to training, teachers received a range of support to protect their health and wellbeing, and to motivate them during these difficult times. Thirty-nine (39) out of 40 countries prioritized teachers as frontline workers for protective measures including vaccination and provision of PPE. Teachers were also protected by measures that reinforced social distancing, or provided on-site care for pupils and teachers, to limit their exposure to illness. Some countries also offered psychosocial support to teachers and pursued a range of measures to address the stress and burnout associated with their increased workload. To prevent all teachers – with or without underlying conditions – from contracting COVID-19, Cameroon, Eritrea, The Gambia, Nigeria, Senegal, and Zimbabwe utilized distance communication channels to reach out to them during training sessions. In Ethiopia, teachers were supported in conducting safe home visits and remote monitoring of student progress. Cabo Verde developed a learning design in which distance education complements face-to-face learning during school closures and when schools reopened, to help curb teacher infections and create a safe learning environment.

Teachers Motivation and Incentives

Some 18 countries provided some form of incentive to offset teachers’ job losses or increase their motivation. These incentives ranged from salary guarantees and other financial incentives, to the provision of airtime credits or Internet bundles to support them in offering distance education.

In South Sudan and Somalia, teachers received financial support to maintain their livelihoods during the pandemic. In Somalia, each teacher received US$100 per month to help cushion them from the adverse economic effects of COVID-19. In Malawi, school return policies saw teachers in grant-aided schools returned to the schools they had taught in prior to school closure. This was to avert further financial loss being incurred by these teachers, who otherwise may have been rendered jobless during the school closures. In Burkina Faso and the Central African Republic, governments and in-country development partners offered reimbursement fees or remuneration to teachers and supervisors who took part in the production and dissemination of distance learning content.

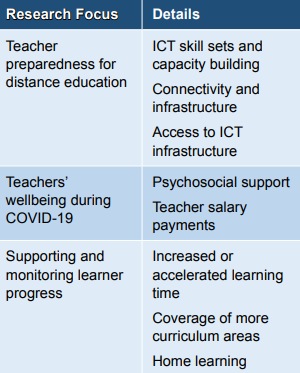

Emerging Evidence

Emerging evidence on teacher training during the pandemic response relates to three main merging evidence on teacher training during the pandemic response relates to three main areas:

- the lack of teacher preparedness for distance education,

- the challenges to teachers’ social and economic well-being during COVID-19

- and best practices in supporting and monitoring learner progress.

The following are some key policy recommendations to the GPE partner countries to better support teachers in facing the COVID-19 pandemic and future crises.

Invest more resources in teacher training to enhance pandemic-coping mechanisms, reverse learning losses, and build back better in education.

Explore public-private partnerships with digital service providers to expand digital access and facilitate the use of DLS in training and learning.

Explore the best ways to train teachers in using DLS to assess and provide feedback and guidance to learners during emergencies.

Prioritize strengthening teachers’ capacity, as frontline workers, to respond to the needs of vulnerable school children within their communities.

Incentivize teachers by addressing the challenges that hinder their performance – providing adequate teaching resources, PPEs, and monetary incentives, and rewarding those who make noteworthy efforts.

Institutionalize a system that enhances teachers’ wellbeing during emergencies – including through psychosocial support.

You can download the full report here: https://www.adeanet.org/en/publications/policy-brief-teacher-training-support-africa-during-covid-19-pandemic