By Steven Blum, copywriter ICWE

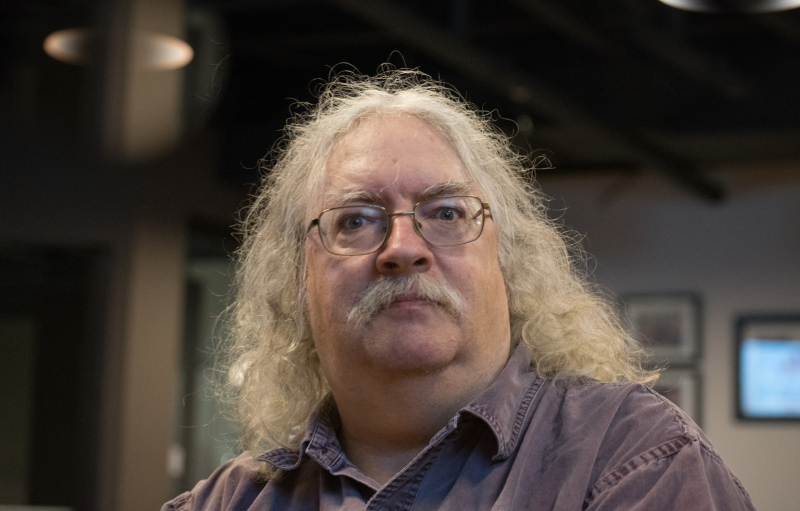

When Stephen Downes and George Siemens, a pair of Canadian academics, began building the world’s first massive open online course (or MOOC) back in 2008, they weren’t exactly expecting massive success.

“We thought maybe twenty people would show up,” Downes recently told me.

They ended up with 2,200 virtual students— a then-massive amount. Thankfully the course, which explored connectivist learning theory, was able to accommodate the influx because it had been thoughtfully built by the pair as a “distributed network of interconnected resources.”

“Because we designed it in a decentralized way, 2,200 people fit nicely,” Downes says. The course utilized a Moodle for formal content, a Wiki for building out knowledge, and a tool called Grasshopper, which Downes had personally built as an aggregator, content management system and mailing list.

Today, of course, other technologies come into play when building a successful MOOC, many of which Downes will be exploring during his upcoming workshop at the eLearning Africa Conference in Côte d’Ivoire next month. A prolific commentator on all things technology and education, Downes keeps tabs on all the latest innovations in his newsletter OLDaily. He’s most excited about how technologies like AI, blockchain, cloud technology and artificial intelligence will revolutionize the ways we learn.

Take AI — not only could the technology recommend content to learners based on their needs, he says, it could also create resources as-needed on the fly, whether that means writing an article for students to read or an instruction manual for them to follow.

Blockchain, too, offers a unique value to educational institutions: because the cryptography is resistant to any form of modification, it’s perfect for credentialing students. When Downes offered a MOOC this year from the National Research Council, he awarded digital badges to students based on their completion of each of his course’s nine units, and then stored those badges on a secure blockchain. “The benefit is that it offers greater credibility,” he says. “No one can come along and try to change it.”

This level of security could end up becoming most crucial in developing nations, where the verification of one’s qualifications is even more important, Downes says.

In fact, all of the technologies primed to revolutionize education could be especially impactful in areas with fewer resources. Whether by developing local cloud technologies (to save money on international bandwidth) or utilizing open data (to save money on course materials), governments and research institutions in Africa can meet and exceed their educational and training goals without breaking the bank by adopting the latest digital technologies.

In many ways, that was the point of Downes’s first MOOC— with its emphasis on “open,” it was meant to democratize learning. As organizations like Coursera and EdX have sought to monetize their offerings, some of that ethos has been lost.

“In the rest of the world, the model is more similar to the original connectivist MOOCs,” he says. “It’s not so much an effort to replicate a traditional course, but to create a community that can investigate for itself some discipline or area of study.”

Connectivism might sounds like a crunchy Silicon Valley buzzword but it actually describes a theory of education in which knowledge is distributed across human and nonhuman nodes in a network. As a Slate article put it, success in a connectivist mode of education means the ability to “navigate this network, link disparate fields, and contribute to the understanding of other people.”

“It’s a lot more learner-focused and a lot less formal, and that’s the model we’re seeing globally,” Downes says.

It’s also a way to think about the future of online education, which is in constant need of infusion of new technologies to stay fresh and interesting. MOOC practitioners can make their courses ever more relevant by linking disparate technologies to their courses of study.

“The benefit here is in savings and, of course, employability, creativity, entrepreneurship, the list goes on. Just look at how India developed its own technology industry by giving many people access to open learning resources in this very informal, loose way.”

Downes is excited to share these case studies with a new crowd in Africa, although he’s careful to note that he’s sharing, not prescribing, what different communities should do—that would be something he says he “isn’t qualified” to do. Most of all, coming to eLearning Africa, he says, will give him a chance to hear voices that “aren’t represented in Europe or North America.”

“All the infrastructure we take for granted here in Canada can be a challenge when you’re working in Africa — everything from power to internet access to physical and cyber security, The last thing I’m doing is going in there say you should do it this way; that’s not my purpose. I’m just there to say, ‘Here is some new and exciting stuff that’s happening around the world, and here’s how it could impact the future of education.’”

Join world-renowned Stephen Downes in his journey to explore the next-generation learning technology landscape: his Workshop Distributed Learning Technologies and Next Generation E-Learning can be attended at eLearning Africa 2019, on Wednesday, October 23.

Take a look at the eLearning Africa 2019 programme here.

We have benefited the subject thanks

I love the idea of a poll

Africa needs a lot of such technology for developing the continent.

Africa needs a lot of such technology for developing the continent.

I wish to be there for the upcoming conference. I am sorry we are still in the process to build our website.